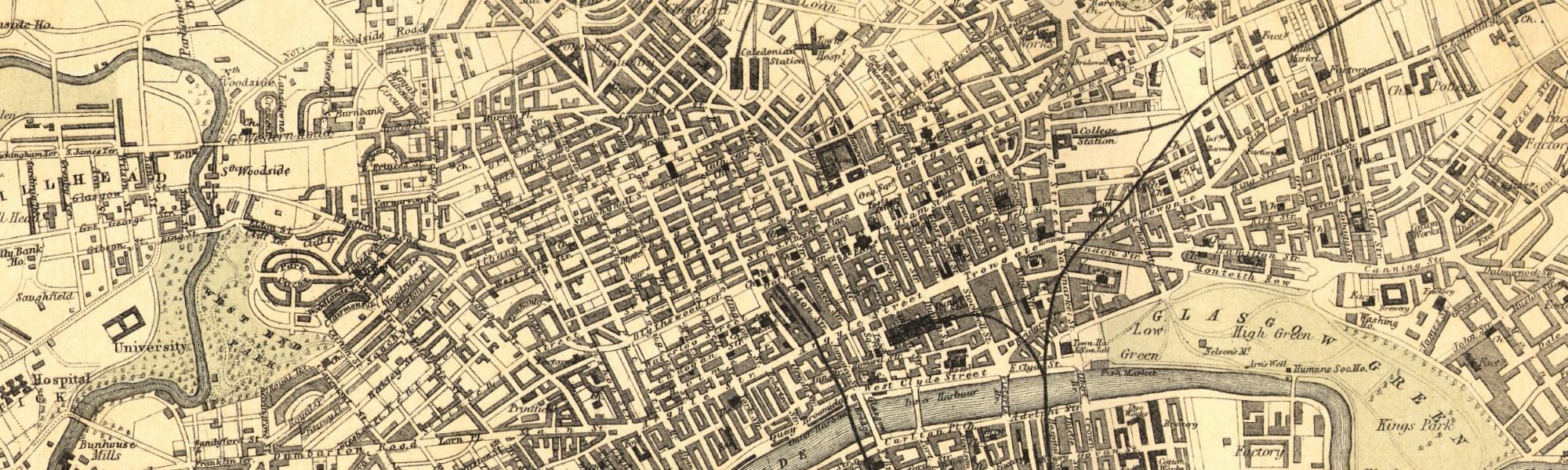

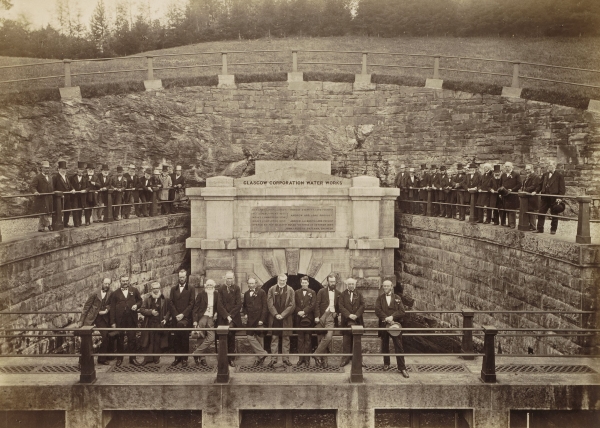

Trades House monument (photograph: Gill Newton)

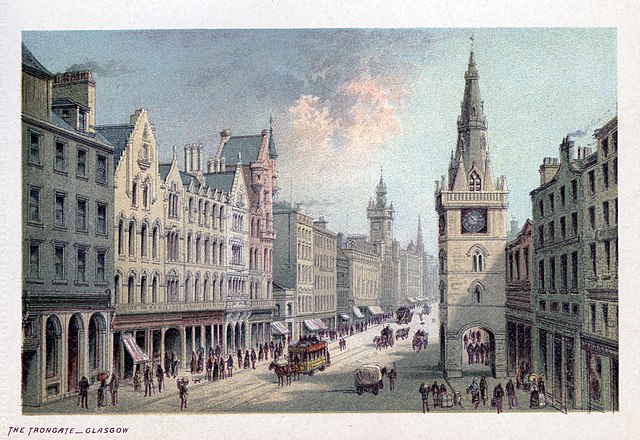

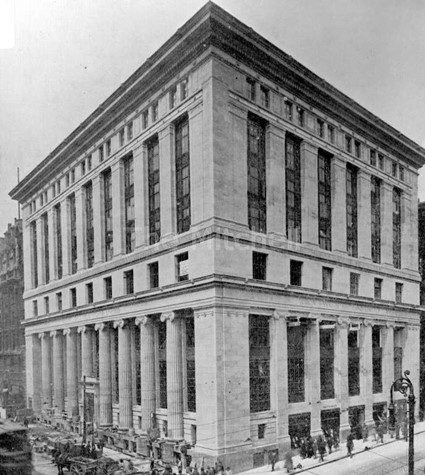

We now stand outside a monument to Glasgow’s trades: look to the left down the passageway and you will see Trades House, home to the trade guilds of Glasgow.

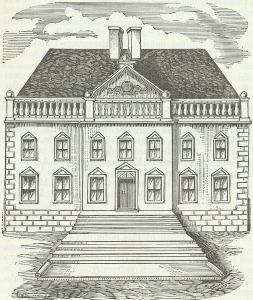

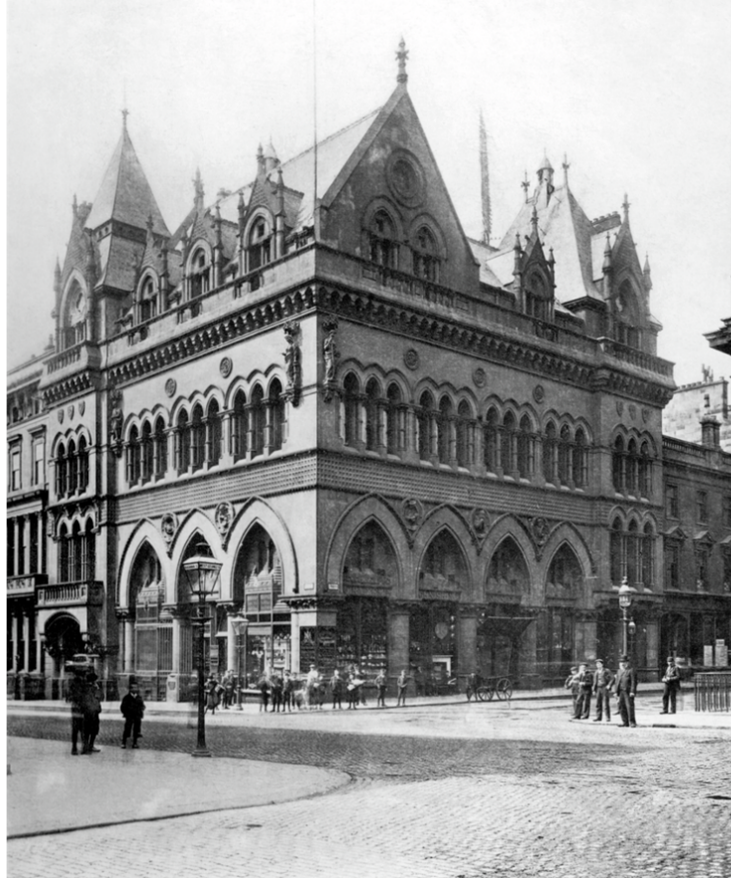

Trades House (right photograph: Gill Newton)

A guild is an association of craftsmen or merchants that formed to protect and further their interests. They, to all intents and purposes, operated a monopoly on who was allowed to trade in those crafts in the city. If you were not a member of the guild you were not permitted to trade.

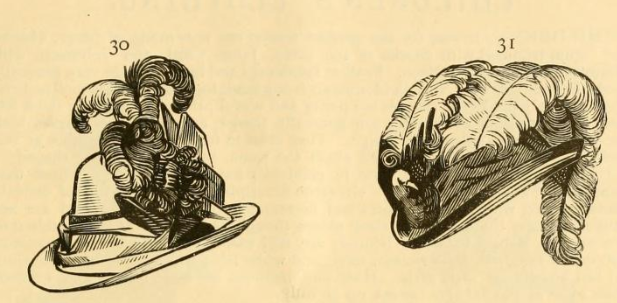

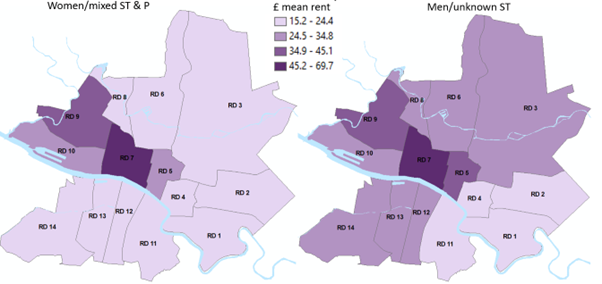

Guilds invested large sums in lobbying governments and political elites to maintain their rights.[1] The trade guilds of Glasgow covered fourteen crafts and included: the hammer men (metalworkers), wrights (skilled carpenters), fleshers (butchers), barbers (medical practitioners), and bonnet makers and dyers.

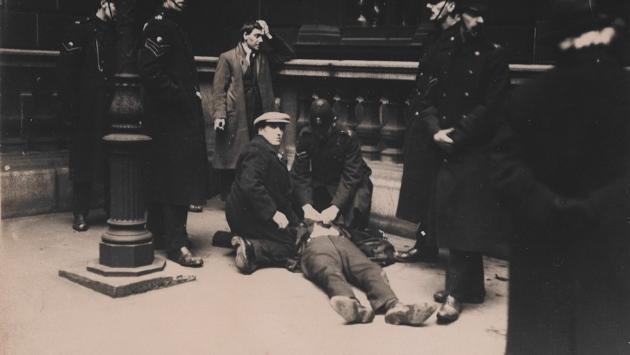

Guild crest of the Hammermen (Harry Lumsden: History of the Hammermen of Glasgow, 1912). The guild originally comprised craftsmen associated with metalworking – for example blacksmiths, goldsmiths, armourers, sword-makers, clockmakers, tinsmiths and other similar activity.

Like many other European societies, guilds in Scotland had considerable influence until the late eighteenth / early nineteenth century.[2] In Scotland, the right of the guilds to claim exclusive privilege over trading in burghs was abolished in 1846.

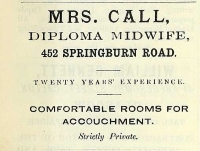

By this time the nature of production was changing considerably, and the traditional apprenticeship structure of training could not keep pace with changes in the labour market. Today Trades House is a charity focusing on both educational initiatives and supporting people in need.

Guilds were vulnerable to changes in how goods were manufactured or produced. Through scaling up the size of operations, businesses produced goods in higher volume more efficiently, and were increasingly developing economies of scale.

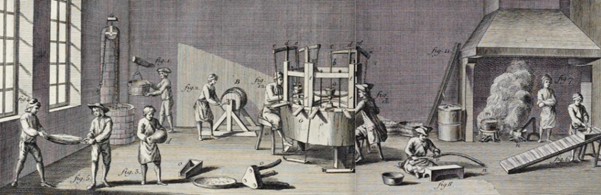

They were taking advantage of the productive powers of the division of labour that Adam Smith (Glasgow’s - if not the world’s - most famous economist) had outlined almost a century before.

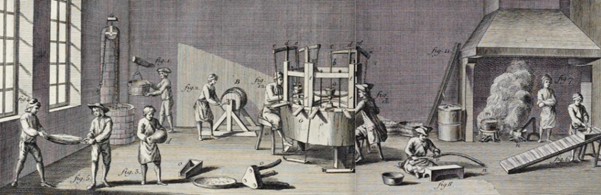

The pin factory (engraving: Robert Bénard in Diderot & D’Alembert: Recueil de planches, sur les sciences, les arts libéraux, et les arts méchaniques, Vol. 4,1762, Epinglier pl. III). Described by Adam Smith in The Wealth of Nations (1776) when outlining how the division of labour into specialized tasks could speed up production and increase profits

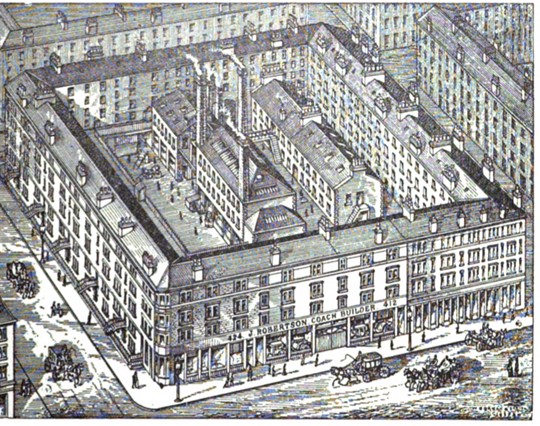

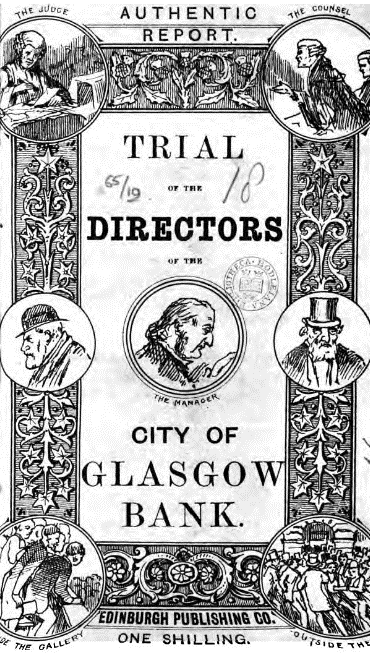

Scaling up was facilitated by changes in business law. Incorporated companies became easier to set up. They had a legal existence and resources separate and potentially ring-fenced from the personal assets of their founders (limited liability). They could also raise large sums of money from many individuals through shares.

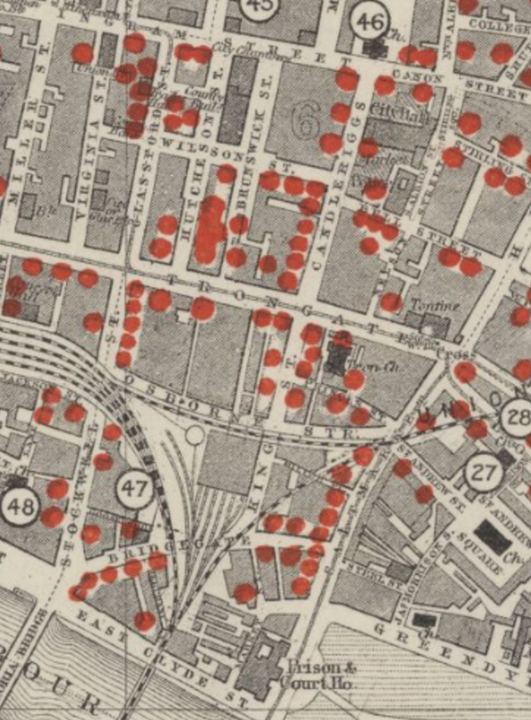

Trade directories show that incorporation was on the rise - there was a trebling in business corporations with a presence in Glasgow between 1861 and 1881. But partnerships that simply pooled individual partners’ assets and required no legal declaration remained the most important large business form until the very end of the 19th century. Many partnerships started out as family businesses and introduced other partners to keep the business going, eventually becoming corporations in the 1890s.

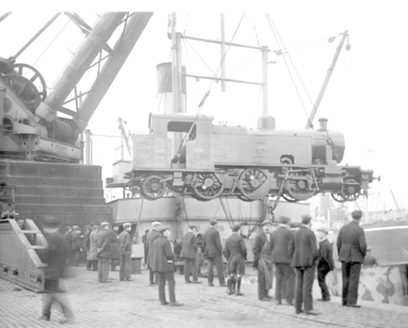

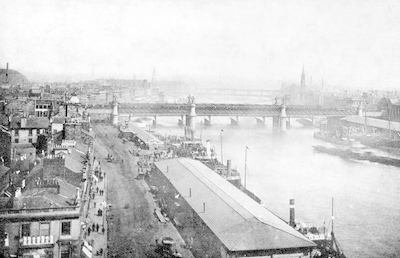

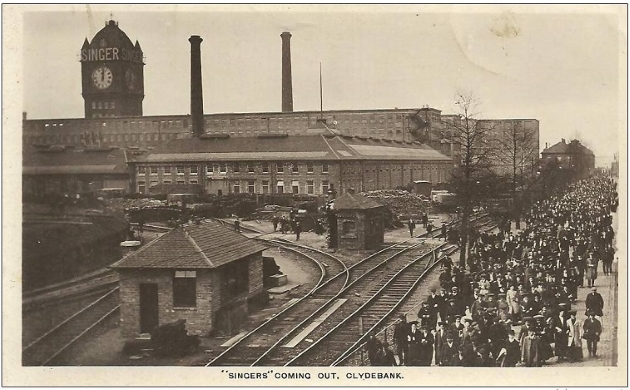

On a scale that would perhaps have been unimaginable even to Adam Smith, The Singer Manufacturing Company’s factory in Glasgow was one of the world’s best examples of scaling up at the start of the twentieth century.

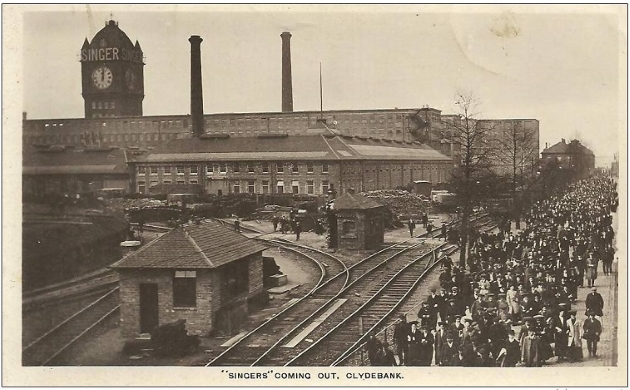

The Singer factory on Clydebank circa1900 (image: Wikimedia Commons)

Employing almost 15,000 people at its peak, it produced over a million sewing machines a year in the decade before World War I. Sewing machines became essential items in millions of households worldwide. Early models were beautiful and substantial pieces of furniture, as well as functional labour-saving devices that sped up the drudgery of hand-sewing clothing and furnishings.

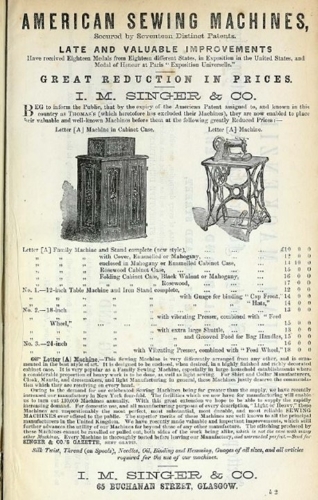

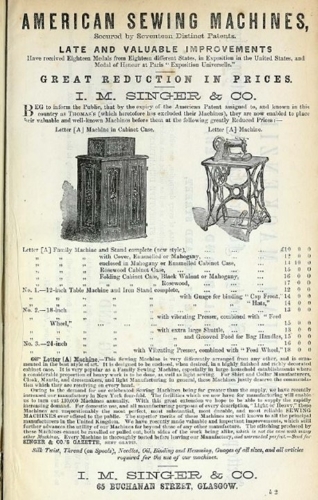

Glasgow 1861 Post Office Directory Singer advertisement (National Library of Scotland)

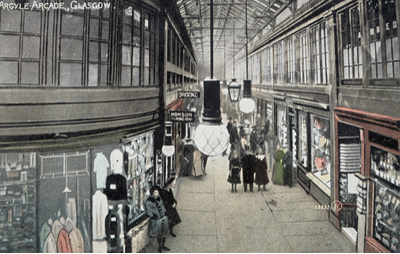

An American company founded in 1851, I. M. Singer were already advertising their sewing machines in Glasgow Trade directories by 1861. Singer built their first dedicated sewing machine factory in Europe here in the manufacturing district of Bridgeton, east of Glasgow Green at 116 James Street in 1869.

Glasgow was selected as a location for the factory because of a combination of the availability of relatively low cost, highly skilled labour, and also its shipping links to the world. As production grew and Singer became one of the largest manufacturing companies in the world, they expanded to west of the city in the 1880s, opening the new factory at Clydebank to meet global demand for sewing machines. [3]

[1] Ogilvie, Sheilagh. ‘Guilds and the Economy’ Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Economics and Finance. Retrieved 10 Apr. 2024, from https://oxfordre.com/economics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190625979.001.0001/acrefore-9780190625979-e-538

[2] Ogilvie, Sheilagh. "The economics of guilds." Journal of Economic Perspectives 28, no. 4 (2014): 169-192.

[3] Se. Godley, Andrew C. “Pioneering Foreign Direct Investment in British Manufacturing.” The Business History Review 73, no. 3 (1999): 394–429.

We now move to STOP 9 - Hutcheson's hospital

![]()